AI and the Creative Process

AI and the Creative Process

by Barry Braverman

For cinematographers, editors, screenwriters, and others involved in creating content, the question inevitably arises: What will become of creators as AI overspreads the broadcast and entertainment industries? What will be the reaction of the public when it finally happens, when computers’ works receive Academy Awards and land an all-AI-generated exhibition at MOMA?

Notwithstanding the current concern and alarm, the fact is that artificial intelligence will never fully emulate human creativity. Quite simply, the process of creating compelling music, fine art, or a TV show, is anathema to a generalized solution powered by a machine-learning algorithm. Indeed, some of us can recall, not so fondly, an AI application from decades that claimed to be able to generate at will a ‘hit’ pop tune. Making use of machine-learning and AI, the 1989 Master Tracks program did in fact generate the notes and simple chords of a potential pop hit, but when asked to ‘humanize’ the work in the final pass, the then-primitive AI process failed miserably. In the end, the program could only succeed in creating the work of a human making substandard music and performing it very badly. The result, in the end, was a facsimile of a creative work, and a vastly inferior one at that.

Today, of course, the sophistication of machine-learning and generative AI far exceeds the crude capabilities of 35-year-old software. But the lesson still resonates. The creative process is inherently undefinable and full of nuance. There is no logic to it. Ultimately, the wit and whimsy of the human artist cannot be fully emulated in a generalized software solution.

For cinematographers, editors, and content creators in general, the promise and benefits of artificial intelligence lies in the tools we use every day. Thanks to the recent advances in machine-learning, our latest-generation cameras feature auto-focus systems that can, among other things, distinguish between the sky and the side of a building, a lamppost from a human being, and the eyes from the nose of our star actress.

In the rapidly evolving realm of AI-powered software, Adobe, for one, is applying artificial intelligence in a big way, taking advantage of its Sensei-machine learning to facilitate and accomplish a wide range of tasks, from removing unwanted elements in frame to organizing one’s résumé. It’s worth repeating that such tools as remarkable as they are, do not replace the human element. Rather, one can think of AI-enabled software as only a starting point for one’s creativity. Like the default drop-shadow setting in Photoshop, the viewer can feel, if not readily identify, the clinical hand of rudimentary machine input. It is up to the user, the artist, to add the human quality that no software or machine-learning algorithm can approach.

The integrated Enhance Speech feature inside Adobe Premiere Pro can help transform substandard audio into something akin to a proper studio recording. Content creators can dramatically improve the quality of problematic audio recordings, including audio that was previously thought lost and unusable.

Is On-Board Camera Recording Dying?

Is On-Board Camera Recording Dying?

With the advent of camera-to-Cloud recording, will in-camera recording media be relegated to the dust bin of history alongside the Jaz Drive and the Sony Memory Stick?

One way or the other, most DPs will soon have to grapple with the challenges of remote image capture. Growing increasingly more practical owing to the efforts of Adobe’s Frame.io and others, working pros across a range of genres will have to confront the profound changes in workflow as industry practice aligns with the technology of direct camera-to-Cloud recording and remote storage.

For DPs and other content creators, the question then becomes: Is on-board, on-set recording media, memory cards, and SSDs, relics of a bygone era?

Michael Cioni, Adobe’s Senior Director of Global Innovation for Frame.io, certainly thinks so. By 2026, he says, virtually every professional camera will feature a camera-to-Cloud capability, utilizing, at the very least, low-bandwidth proxies. By 2028, thanks to 5G, Cioni foresees global bandwidth expanding sufficiently to capture and upload RAW files in real time. And by 2031, Cioni predicts that pro level cameras will no longer feature any on-board recording capability at all! The camera’s sole storage function will be limited to its massive buffer uploading continually to the Cloud.

Such fundamental changes in industry practice have happened before: the transition from film to digital and from standard definition to HD are two instances that readily come to mind. These transitions occurred over the course of a decade, and the camera-to-Cloud transition will likely require a similar time-frame as DPs and production entities consider the feasibility and relative merits of a C2C network workflow.

Some old habits, of course, die hard, but this one, obviating the need for physical media does not appear to be one of them. The instant sharing and enhanced collaborative opportunities among far-flung members of a production team are undeniable benefits, as does the ability to provide redundancy and certain security measures like a watermark during upload. The time-saving advantages of direct-to-Cloud recording is obvious, given the no longer the need to upload and download terabytes of data from physical media drives.

For DPs, a new way of working must be simple and convenient. Any new technology that is too complex or difficult to access will be overlooked and forgotten, regardless of the supposed economic benefits and feature set.

Recognizing this, Frame.io is pushing camera manufacturers to integrate Network Offload as a simple menu option. Currently, such an option is limited to the RED V-Raptor, but this will no doubt change as manufacturers like Sony and Canon recognize the merits of C2C.

Ultimately, whatever workflow is adopted by professionals, whether local or Cloud-based or a hybrid of the two, it will come down to the entertainment value of the more compelling stories that can be delivered to viewers, and monetized in the streaming environment.

Do We Still Need Green Screen?

Do We Still Need Green Screen?

With the advances in artificial intelligence, post-production rotoscope tools are now so good that some DPs are asking if we still need to use green screen at all, or at least, in quite the same way.

Suddenly, it seems any background can be replaced in seconds, allowing DPs to shoot the most complex compositing assignments faster and more economically. Today’s AI-powered rotoscoping tools are powerful and robustl as producers can repurpose a treasure trove of existing footage packed away in libraries and potentially reduce the need for new production or costly reshoots.

In 2020, Canon introduced the EOS 1D Mark III camera for pro sports photographers. Taking advantage of artificial intelligence, Canon developed a smart auto-focus system by exposing the camera’s Deep Learning algorithm to tens of thousands of athletes’ images from libraries, agency archives, and pro photographers’ collections. In each instance, when the camera was unable to distinguish the athlete from other objects, the algorithm would be ‘punished’ by removing or adjusting the parameters that lead to the loss of focus.

Ironically, the technology having the greatest impact on DPs today may not be a camera-related at all. When Adobe introduced its Sensei machine-learning algorithm in 2016, the implications for Dos were enormous. While post-production is not normally in most DPs’ job descriptions, the fact is that today’s DPs already exercise post-camera image control, to remove flicker from discontinuous light sources, for example, or to stabilize images.

In 2019, taking advantage of the Sensei algorithm, Adobe introduced the Content Aware Fill feature for After Effects. The feature extended the power of AI for the first time to video applications as editors could now easily remove an unwanted object like a light stand from a shot.

The introduction of Roto Brush 2 further extended the power of machine learning to the laborious, time-consuming task of rotoscoping. While Adobe’s first iteration used edge detection to identify color differences, Roto Brush 2 used Sensei to look for uncommon patterns, sharp versus blurry pixels, and a panoply of three-dimensional depth cues to separate people from objects.

Roto Brush 2 can still only accomplish about 80% of the rotoscoping task, so the intelligence of a human being is still required to craft and tweak the final matte.

So can artificial intelligence really obviate the need for green screen? In THE AVIATOR (2004), DP Robert Richardson was said to have not bothered cropping out the side of an aircraft hangar because he knew it could be done more quickly and easily in the Digital Intermediate. Producers, today, using inexpensive tools like Adobe’s Roto Brush 2, have about the same capability to remove and/or rotoscope impractical objects like skyscrapers with ease, convenience, and economy.

For routine applications, it still makes sense to use green screen, as the process is familiar and straightforward. But the option is there for DPs, as never before, to remove or replace a background element in a landscape or cityscape where green screen isn’t practical or possible.

Can AI-powered rotoscoping tools like Adobe’s Roto Brush really replace green screen? Some DPs think so, especially in complex setups such as many cityscapes.

Roto Brush has learned to recognize the human form, and is thus able to isolate it, frame by frame, from a background. But even with the power of AI, Roto Brush still requires some human input.

[Screenshot from CM de la Vega ‘The Art of Motion Graphics’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uu3_sTom_kQ]

.

Is Post-Production Our New Livelihood?

Is Post-Production Our New Livelihood?

For the last decade, in the halcyon years before COVID, documentary, corporate, and other non-fiction DPs, were already assuming a greater role in post-production. Whereas frame rates, f-stops, and the character of lenses, once formed the backbone of our expertise and practice, DPs in the non-theatrical realm increasingly find ourselves in a much different kind of role, performing tasks that seem an awful lot like post-production.

The advent of the smartphone camera has had a lot to do with it, as mobile editors like LumaTouch’s LumaFusion regularly remind us of the device’s plethora of impressive capabilities.

With the transition to IP and remote production, non-fiction DPs have had to embrace the new normal, which increasingly includes a significant post-production role. We already use a range of post-camera tools to perform image-control tasks, like removing the flicker from discontinuous light sources or stabilizing shaky, handheld scenes. Now, beyond the exigencies of image remediation, we are moving into a creative role, selecting takes and compiling footage, and even delivering a quasi-finished edited program while still in the field.

It isn’t that DPs are forsaking cinematography in favor of a cushier, sit-down life as ersatz editors. Instead, it’s more about the kinds of projects we are apt to pursue these days, and who is paying for them.

I recall my BTS work on the Lethal Weapon franchise in the 1980s and 1990s, and my assignments couldn’t be more straightforward. Commissioned by Warner Bros. and HBO, I would shoot content in and around the set, including interviews with the director and talent. I would then furnish the raw footage on videocassette to the editor, who would work with a writer to assemble the finished show. In other words, DPs shot, writers wrote, and editors edited.

A decade later on films like The Darjeeling Limited and Moonrise Kingdom, my behind-the-scenes deliverables had expanded dramatically. By now, the studio’s publicity department had split into mini-fiefdoms of home video and DVD, marketing, and special projects – all of whose chiefs and czars contributed to, and played a role in, overseeing my BTS content. The Web and the immediacy it demanded a two or three-minute program daily for posting on the studio website, distribution to the press, and dissemination across social media – all the while operating on a moving train or in a tiny hotel room thousands of miles from home.

A quick pan around corporate and news magazine sets these days and the trend couldn’t be clearer: Remote IP production is obviating the need for large investments in pricey infrastructure. A humble facility in our garage can receive live inputs from a multitude of sources from mobile phones, iPads, computer screens, and whatever else we have lying around in the IP arena. Understandably, producers look around the set and who do they see, looking competent and confident? That’s right. Rightly or wrongly, producers conclude that logically it makes sense for DPs to do it all.

****

Shooting behind-the-scenes for feature films? Be prepared to assemble a featurette, podcasts for the studio website, and an electronic press kit (EPK). And oh yes. You may also need to provide a live stream directly from the set.

Mirrorless Cameras Come of Age

Mirrorless Cameras Come of Age

The elimination of the mirror box from DSLRs brings significant benefits to shooters, as evidenced by the raft of new full-frame cameras around, like the Panasonic Lumix S1, Sony Alpha 7, Canon EOS R – and the Nikon Z6.

The 24Mpx Z6 features a full-frame ‘Z’ 55mm mount – the widest available of any DSLM [digital single lens mirrorless]. This enables Nikon to more efficiently utilize the full width of the camera sensor. More practically for shooters, the elimination of the mirror box enables lens manufacturers to produce more compact, lighter weight zooms because the lens mount can be placed further back closer to the sensor.

Nikon’s shallow 16mm flange focal distance is the shortest among the major DSLM manufacturers. For shooters, this means that Nikon’s ‘S’ wide-angle zooms can be made with a less bulky front element group – a welcome development for shooters feeling burdened by the front-heavy optics of the past.

The 58mm Nikkor Z f/0.95 Noct lens produces truly amazing full-frame pictures; the lens creates a distinctive flare and coma around point sources that gives shooters a wide range of new options along with an extremely narrow depth of field.

There’s an easier, better way to shoot HDR.

There’s an easier, better way to shoot HDR.

High Dynamic Range (HDR) and Wide Color Gamut (i.e.BT.2020) is all about managing a much wider range of light levels and color. Consumers may marvel at their spanking, new 4K TVs, but what they really see and appreciate is HDR’s more compelling pictures. Increased resolution plays a role, increasing the apparent detail in both highlights and shadows, but resolution is not the whole picture when it comes to producing the optimal viewer experience.

Top-end DPs and DITs on set typically utilize a three-screen strategy for capturing HDR. The typical workflow comprises a waveform, vector display, and dual HDR-SDR monitors, like the Sony BVM HX310 and Sony BVM E171, for side by side comparison. In practice, this approach can be awkward and extremely inconvenient.

Beyond that, the toggling of monitors is not particularly informative, especially when viewed from afar across a busy set. Needless to say, DPs have a lot to think about , so the constant toggling of monitors comparing the HD and SDR signals should not be the priority.

The current approach employing dual monitors is also subjective, as it is highly dependent on the ambient viewing conditions. Stray light from a ceiling fixture or desk LED can strike the face of a monitor, and skew a DP’s assessment.

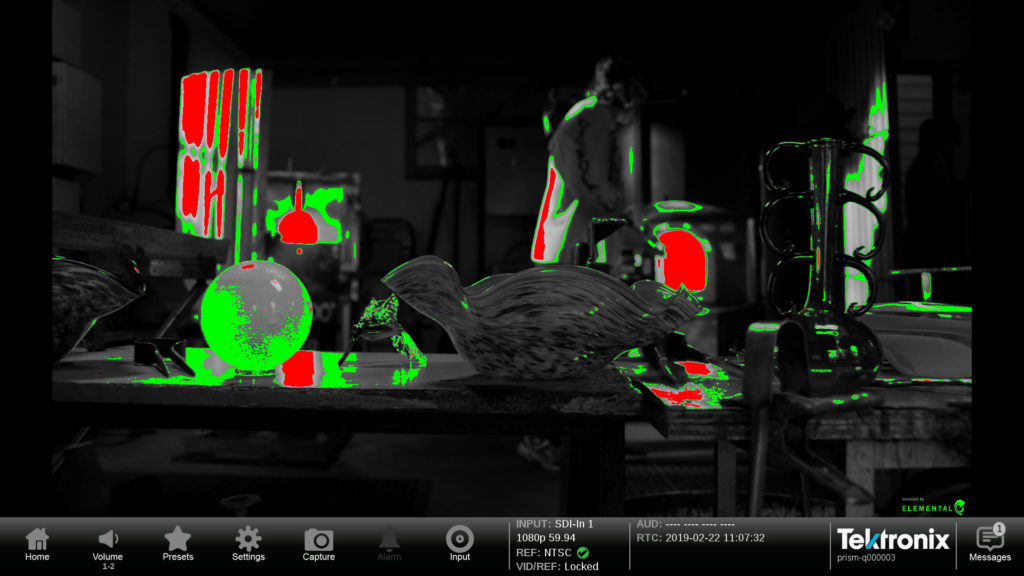

Ultimately, a single luminance-based reference monitor is way to go. The system, promoted notably by Tektronix, applies an HDR conversion LUT that converts light level voltages to nits so a DP can more easily relate to the waveform display. Depending on the graticule selected, DPs can spot areas of potential clipping, and assess how elevated the highlights actually are in a scene: Are they1000 nits? 4000 nits?

Today, DPs must know the highlight values in the expanded HDR range, and to accomplish this, DPs can work from a waveform displaying in either nits or stops. Working typically with the log output from cameras like the ARRI Alexa, the luminance in stops may be adjusted, simply and predictably via the lens iris. If the inputted signal is Hybrid Log Gamma (HLG) or Perceptual Quantizer (PQ), the display mode of the waveform should be set to nits.

A good practical HDR setup features a dual-display with the main waveform and two smaller HDR-SDR insert waveforms. This layout has the advantage of displaying both the HDR and SDR waveforms simultaneously, to confirm they are the same shape and their highlights fall approximately in the same area. The DIT may choose to display a CIE chart as well to ensure there are no out of gamut color areas,

The key to this is a single monitor displaying false color luminance values . While monitors are capable of displaying values for up to ten regions, most DPs, for ease of visibility, will opt to display only three or four colors. Using the ARRI luminance colors as a reference, we would typically assign blue or cyan to 18% grey (17-26 nits in the HDR-HLG environment), reference white to 180 nits, yellow and orange to represent values from 180 to 203 nits, and red to brightness areas above 203 nits to indicate values outside SDR range. Once the scene’s light levels and camera stop are determined, the harried DP need only need reference the false-color display to verify all is well.

Assigning false colors to the LogC output from an ARRI Alexa may typically produce the following luminance values:

Magenta: 0.0000 – 0.1002

Blue: 0.1002 – 0.1223

Green: 0.3806 – 0.4014

Pink: 0.4523 – 0.4731

Yellow: 0.9041 – 0.9290

Red: 0.9290 – 1.0000

Can the iPhone Replace a $20,000 Camcorder?

Can the iPhone Replace a $20,000 Camcorder?

With the introduction of Apple’s iPhone XR and XS models, the mobile do-everything wünderdeviceis are again drawing attention as a viable alternative to a traditional video camera. In feature films, the iPhone is already being used as in Steven Soderbergh’s UNSANE (2018), starring Claire Foy. Soderbergh is quoted as saying re that experience: “I look at the iPhone as one of the most liberating experiences I’ve ever had as a filmmaker.”

The iPhone’s lens may seem crude but it is capable of producing startlingly high-resolution images owing to the corrective algorithms applied in the iPhone’s software. The efficiency of the correction is remarkable for its ability to correct egregious lens defects like barrel distortion and chromatic aberrations, the latter being the main reason that cheap lenses look cheap.

There are limitations inherent to utilizing the iPhone for advanced image capture. Its 3mm sensor, with pixels only a few microns in diameter, is notably unresponsive in low light, which means iPhones invariably exhibit poor dynamic range. In the wake of iOS 12 and Apple’s new XS and XS Max, however, shooters are seeing improved log and flat gamma responses, as much as 2.5 stops of additional dynamic range when utilizing FiLMiC Pro’s Log v2 software.

The iPhone, depending on the model, is capable of capturing scenes from 1-240 FPS. FiLMiC Pro adds the ability to set frame rates in increments of a single frame. With the latest update, FiLMiC Pro outputs high bitrate files up to 150Mbps for editing in LumaFusion – the most capable, professional mobile editor on the market.

FiLMic Pro provides shooters with familiar essential functions like focus peaking, zebra stripes, false color, and clipping overlays. The inexpensive app ($15) allows manual control over focus, white balance, zoom speed, and exposure. The ability to control exposure is key as shooters and lighting designers can tweak the look of a scene around a desired ISO and shutter speed.

FiLMiC Pro’s Log v2 expands the dynamic range of the newest iPhones to 12 stops, while producing a 10-bit file for effective color-grading. While the iPhone can only capture video at 8-bits, Log v2 processes the luma and chroma components of the iPhone video with 64-bit precision. The result is an enhanced dynamic range with a smooth tonal quality that bypasses, at least to some extent, the constraints of the iPhone’s 8-bit video. Given the expanded gamma, Log v2 is most effective and noticeable in the mid-tones, with less impact in the luminance areas at or near the black or white points. Log v2 works on all iOS devices, and most Android camera 2 API-capable phones and tablets.

Steven Soderbergh’s UNSANE (2018).

Does the Continuously Variable ND Filter Spell the End of the Lens Iris?

Does the Continuously Variable ND Filter Spell the End of the Lens Iris?

The advent of the continuously variable neutral density filter (VND) raises an interesting issue: Do we still need a lens iris at all? The iris ring and underlying mechanism fitted with fragile rotating blades are at constant risk of damage from shock, moisture, and dust penetration; the iris itself adding cost and complexity while also reducing sharpness from diffraction artifacts when stopped down. The new Sony FS7 II features a VND that isn’t quite efficient enough to eliminate the lens iris entirely – but the day may be coming. For shooters, this could mean much better performing and sturdier lenses at lower cost.

The Sony FS7 II VND offers insufficient light attenuation to eliminate the lens iris entirely – but the day may be coming.

Exercise Your SSDs! Like Any Other Storage Drive

Exercise Your SSDs! Like Any Other Storage Drive

When designing a drive, engineers assume that some energy will always be applied. Leaving any drive on a shelf without power for years, will almost certainly lead eventually to lost data. For those of us with vast archives stored on umpteen drives sitting idle in a closet or warehouse, the failure of a single large drive or RAID array can be devastating.

Mechanical drives are inherently slow, relatively speaking, so moving large files can significantly reduce one’s productivity. Beyond that, the high failure rate of mechanical drives is an ongoing threat. The distance between the platters is measured literally in wavelengths of light, so there isn’t much room for dislocation of the spinning disks due to shock. This peril from inadvertent impact is in addition to the normal wear and tear of mechanical arms moving continuously back and forth inside the drive.

For documentary shooters operating in a rough-and-tumble environment, the move to flash storage is a godsend. SSDs contain no moving parts, so there is little worry from dropping a memory card or SSD while chasing a herd of wildebeests, or operating a camera in a high vibration environment like a racecar and fighter jet.

SSDs also offer 100x the speed of mechanical drives, so it’s not surprising that HDDs these days are rapidly losing relevance. The lower cost per gig still makes mechanical drives a good choice for some reality TV and backup applications, but as camera files grow larger with higher resolution 4K production, the SSD’s greater speed becomes imperative order to maintain a reasonably productive workflow.

Right now the capacity of mechanical drives is reaching the upper limit. Due to heat and physical constraints, there are only so many platters that can be placed one atop of the other inside an HDD. SSD flash memory, on the other hand, may be stacked in dozens of layers; with each new generation of module offering a greater number of bits. Samsung is moving from 256Gb flash chips in 48-layers to 512Gb chips in 64-layers.

So how much should you exercise your HDD and SSD drives? Samsung states its consumer drives can be left unpowered safely for about a year. In contrast, enterprise data drives found in rack servers are designed for heavy use with continuous data loads, and offer only a six-month window of reliability without power. Such guidelines are vital to keep in mind as some shooters may not use a particular drive or memory card for many months or even years, and for them, it is important to power up their SSDs from time to time, to ensure a satisfactory performance and reliability.

One other thing. SSDs have a limited life expectancy. The silicon material in flash memory only supports so many read-write cycles, and will, over time, eventually lose efficiency As a practical matter, the EOL of solid-state drives should not pose much of a problem however. Depending on the load and level of use, most consumer SSDs writing 10-20GB per day have an estimated EOL of 120 years. Most of us I would think will have replaced our cameras, recording media, and storage drives, long before then.

All drives, including SSDs, require regular exercise. Ordinary consumer drives should be powered up at least once a year to maintain reliable access to stored data. Professional series and enterprise-level drives require powering up twice as often, about every six months, to ensure maximum efficiency and long life.

For Better or Worse… QuickTime Exits the Scene

For Better or Worse… QuickTime Exits the Scene

With the introduction of Imagine Products’ PrimeTranscoder, the QuickTime-based paradigm introduced over 25 years ago may finally be changing for video and web-publishing professionals. Foregoing the aging QuickTime engine, PrimeTranscoder utilizes Apple’s latest AVFoundation technology instead, taking ample advantage of GPU acceleration and core CPU distribution, among other tricks. To its credit, PrimeTranscoder supports virtually every professional camera format, from Avid, GoPro, and RED, to MXF, 4K and even 8K resolution files. Underlying this greater speed and efficiency, support for these codecs is completely native, sharing the 20 or so different types also supported inside Imagine’s HD-VU viewer.

Since 1991, Apple’s QuickTime engine has served as the de facto go-between for translating digital media files, enabling manufacturers like Sony, Panasonic, and others, to encode/decode their respective codecs on user devices from editing platforms to viewers. Abandoning the QuickTime engine, PrimeTranscoder is leading the charge, offering the ability to process ProRes and H.264 files more quickly and efficiently, but there is a downside as well. Foregoing the old but versatile QuickTime library greatly complicates support for certain popular legacy formats like MPEG-2. MPEG-2 is still used widely for preparing DVD and Blu-ray discs, especially in parts of Africa and South Asia where Internet connectivity is poor or nonexistent. MPEG-2, like most legacy formats, is not currently supported in PrimeTranscoder.

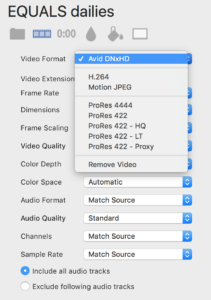

PrimeTranscoder is a new application, and still early in its development. Indeed one key legacy format, Avid DNxHD, has been added to the latest PT release, which Imagine says, without a QuickTime translation, required quite a back flip to accomplish. Like it or not, shooters, producers, and content creators of every stripe, are transcoding more files for a multitude of purposes – for dailies, for streaming, for DVD, for display on a cinema screen. Letting go of the legacy stuff, for all of us, is very hard to do.

PrimeTranscoder’s main window is simple and intuitive. No need to consult a manual or quick-start guide.

Legacy’ formats contained in the QT library like MPEG-2 (for DVD and Blu-ray) are not supported in PrimeTranscoder. The latest PT update does support Avid DNx, so where there’s a will, there’s a way to support the old formats.